Like many first semester students taking the MSLS program here at UKY, I took LIS600. There we are provided with an overview of concepts important to library science, and we are asked to write a series of papers briefly going over a chosen topic. I centered my second paper around the use of folksonomies, or tagging. I compared and contrasted it with traditional cataloging and classification systems like LoC and Dewey. Fast-forward to the present day, and I find myself employing the use of tags in not just this class, but also in LIS665: Digital Libraries, where the final project requires us to apply appropriate tags to each item in our digital library. I suppose the point I’m trying to make here is that tagging is something that has stuck with me throughout my time in this program, and therefore I’ve had ample opportunity to reflect on how I use them. In this blog post I’ll be sharing the tagging/bibsonomy strategies I employed for this course, how they evolved, and how I justify it.

To start, bibsonomy has been a great little tool for me. I could use it to easily cite references used in my papers and blog posts with better accuracy than I could inputting them manually, and served as an ideal means of keeping track of what I had read. I made bibsonomy use a part of my reading routines, having it open while I read so I could immediately add the publication/bookmark after I was finished. The information would be fresh in my mind, so I could use more accurate tags that reflected my thinking of the time. Given that this is my last semester in the program, it’s hard to say how often I’ll come back to bibsonomy, but I do wish I had known about it earlier.

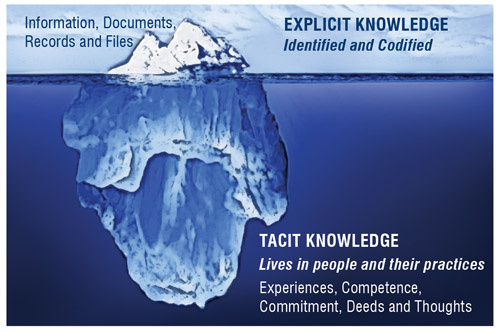

Despite my desire for everything to be consistent, I did not have any formal rules with how I tagged the publications I read. Like I mentioned in a comment on Jenn’s tagging post, I decided early on that it would been more work than I was willing to take on to ensure that all my tags were consistent. In this case, that would have meant using the same vocabulary for the same concepts, a set number of tags for each publication, etc. Folksonomies do not have to be constrained by controlled vocabularies for formal rules, and should serve to supplement such systems. My tagging was organic, and I tagged with words that summed up passages or sections that resonated with me at the time. For example, one of my tags for Polanyi’s book was “iceberg”. When Polanyi first mentions the phrase, we know more than we can tell on p. 4, it reminded me of how I first came across the idea of tacit knowledge. It was used in the context of competitive gaming, in how top players often know much more than they can articulate, and thus have a hard explaining how they got to be so good. The analogy of an iceberg was used, and while I want to say the source of that was David Sirlin’s Playing to Win, going through it again with Ctrl+F isn’t yielding me answers.

The one thing I made sure to do with every publication was to tag it with its category: review, empirical, text, or paper. The first two are self-explanatory, and “paper” was used for sources consulted for this course’s 15-page paper project. “Text” was only used twice, for the class’s two required books. The purpose of this was to keep track of how many in each category I had read to make sure I was keeping pace with the class requirements of 17 “Review” articles, and 16 “Empirical”.

Tags are a great way to casually keep track of one’s digital items, and more than once have I thought how nice it would be if there was a more intuitive way to tag existing documents and pictures saved on one’s hard drive. Maybe I’ll send Microsoft some feedback about it someday…

References:

Polanyi, Michael. (2009). The tacit dimension. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sirlin, David. (2006). Playing to Win. Lulu.com.